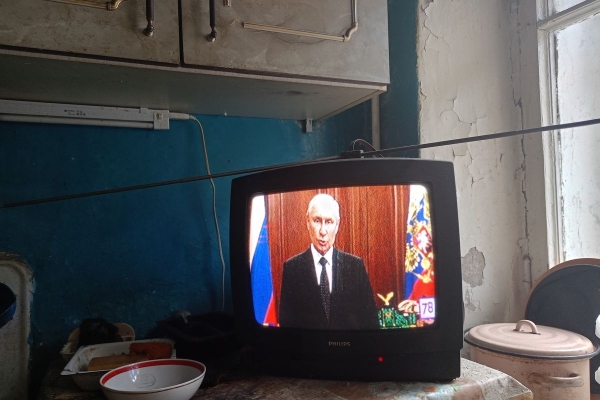

The dramatic weekend of violence Russia — a mutiny that left warlord Yevgeny Prigozhin exiled in Belarus — captured the American media’s attention.

What about those watching the events in Russia?

Almost a year and a half into Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine, there are many lingering questions about how Russians see the country, the invasion, and the future of both. It’s similarly difficult to get the complete picture of how Russians grasp the moves of Prigozhin’s Wagner Group. The country’s press is closed, though VPNs are not uncommon as a way to access independent media. Putin’s security forces have hampered political expression, especially in the past year. Yet there are many indicators of where Russian public attitudes stand and how they are shifting, including public polling in Russia and an active ecosystem of bloggers and social media posters.

To get a better sense of how Russians are interpreting the recent events, I called Maria Lipman, a longtime journalist focused on the country and regular contributor to Foreign Affairs. She’s also a researcher at the Institute of European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies of the George Washington University.

“One thing is already clear now: [There] are desperate attempts by the government, by the loyalists, by state media, national television, to portray the events of 23rd and 24th as victorious for the Kremlin,” she told me.

Lipman and I also discussed why some Russians have ignored the war and why others take risks to stay closely updated on it through independent media. She explained the role of Russian bloggers in supporting the war, how conspiracy theories spread in Russia, and what to watch for between the lines of Russian state media.

In the coming days, Lipman will be watching whether Prigozhin’s rebellion will change the behavior of elites in Russia and those among Putin’s inner circle who can now see more clearly the weakness of the strongman.

Of course, Prigozhin is a brutal leader willing to commit heinous crimes on the battlefield and in keeping his troops in line. But in his media savvy and his political maneuvers, Lipman observes something missing from elsewhere in Russian public affairs. “He doesn’t censor himself, unlike nearly every Russian statesman. His speech is not stilted. He seems to be saying what he truly believes,” she explained. “He comes across maybe as a true patriot, whereas other statesmen come across as groveling to Putin and saying what needs to be said.”

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.

What are Russians thinking about what’s happened?

There’s very little we know about what people think right now. There haven’t been any polls or any surveys, not even locally.

What anecdotal evidence tells us is that in the city of Rostov, where Yevgeny Prigozhin had his headquarters for a while, people were showing sympathy — sympathy to him. And especially as he was leaving the city, there were crowds. Not gigantic, but crowds gathered to greet him and his soldiers. And they were clearly sympathetic, and people were vocal about it.

Again, we’re only talking about small groups of people who gathered, who decided to, actually, despite warnings from the city administration that people better stay home.

Anecdotally also, you see sympathy or expressions of sympathy in the streets. Especially during the days when it was happening, [the] 23rd, especially 24th of June, everyone was reading news. You could see people in the streets or in offices reading news. So there was a lot of interest in the developments and more sympathy with Prigozhin than one might think.

What would people in Russia be reading this week?

There’s actually plenty — as long as one is interested and wants to know more than government mouthpieces have to say, it’s not a problem. Using VPNs is not a challenging skill. Anyone can do it, and the experience of countries such as Iran, for instance, show that VPNs are a reliable means to get read into information that the government would rather bar its people from.

So there are any number of Russian media in exile, because nearly all of the non-government media left Russia after the war began.

There is also this phenomenon of the so-called military correspondents. They are Telegram bloggers, and some of them enjoy very broad popularity, and some of them are critical of the state leadership and the military leadership and the way the war has been waged. There’s been a lot of criticism of that. Those military correspondents stopped short of criticizing Putin personally, just as Prigozhin did up until the 24th of June, trying to refrain from criticizing the commander in chief, the president of Russia. But a critical perception of what is going on at the front has been fairly common.

There are a lot of Prigozhin sympathizers among military correspondents, not all of them. Also Prigozhin has his own Telegram, and he is quite media-savvy. He is known to have launched and managed this troll factory [that was used to sow political discord abroad, including allegedly in the 2016 US election]. He has a news agency; it is known by its acronym FAN, which stands for Federal News Agency, in Russia.

There is easy enough access to alternative information. The question is whether people are really interested in [and] anxious to learn more, which is by far not everyone, of course.

How do people see Prigozhin, and how did that change over this past weekend?

What people know was reflected at the end of May in a monthly poll by Levada Polling Agency, which is the largest non-government polling institution in Russia. Levada Center asks every month: Who are the politicians who you trust? And this is an open question — that is, respondents are not given a list; rather, they are invited, encouraged, to name whoever they want.

Putin, of course, is invariably number one, way ahead of everybody else. Usually after that comes three figures: the minister of defense, minister of foreign affairs, and the prime minister.

For the first time, Prigozhin also featured in this poll in May, so people remembered about him enough to give an answer when a pollster asked them. The actual number is low, but it was the first time he was even listed, and he came in fifth. But this is quite something, in a big country. This means that people are paying attention. And this is not because he’s covered on television. This is because they’re reading alternative sources.

What do Russians really think about Prigozhin, beyond this poll?

Prigozhin is a murderer, a brutal military figure, who claims he has ordered people killed for insubordination. The question is: What do people see in him? Not that, apparently.

He doesn’t censor himself, unlike nearly every Russian statesman. His speech is not stilted. He seems to be saying what he truly believes. Of course, he’s also political and he’s media-savvy, but he comes across as a successful populist.

He comes across maybe as a true patriot, whereas other statesmen come across as groveling to Putin and saying what needs to be said.

And he also can claim a kind of victory, even though from a military standpoint, this victory was probably not very significant. But he’s the only one who can claim victory in the recent months, actually this year, in Bakhmut. He capitalized a great deal on it, saying that he set this goal, or probably Putin set this goal, and he fulfilled it, whereas the minister of defense can do nothing with his troops. So this kind of patriotism has sincerity; it is not stilted patriotism, but genuine.

Again, I would not underestimate the media savvy. And the fact that he has enriched himself immensely. But people probably do not know about it, or probably don’t think about it, that he is, in many ways, one of the elites as well. Because he comes across as different, as fresh, as genuine, as sincere and patriotic.

Where do you see the public view of him going from here, if this poll was conducted prior to the mutiny?

We’ll see. It will be very interesting to see whether his rating will go up as a trusted politician. And what will happen to Putin’s rating as well.

Putin seems to have been steady over time, and the majority have said Russia is headed in the right direction under Putin.

I think the actual number is a bit lower. But there are definitely many more people who believe that Russia is on the right track than those who believe that it is on the wrong track.

Do you think people are nervous to share their actual perspective with pollsters?

You know, this is a problem everywhere. What polls measure is not how people feel; it’s what they choose to say at a certain moment. This is a reservation that should always be taken into account. Same in Russia.

Those who are critical of polling as a method at a time of war in a country that has become increasingly authoritarian, they point to the response rate, which is low in Russia, but not much lower than it is in the US. Which means that when a pollster reaches a person, a person hangs up, or just refuses to answer. But the number of those who agree is low, relatively, and it is low in the United States. It is somewhat lower in Russia, but not essentially so. So this criticism may be relevant. But this does not mean that polls in general, as a method, have become fully non-informative. They are. And also, you know, there’s always a percentage of people who say that they do not approve of the war, or the special military operation, as it’s called.

What is important is if the same question is asked over time. The dynamic is what matters. So you see that, for instance, at the time when Putin called for mobilization, which was in September last year, the number of people who said that they were nervous, alarmed, anxious, went up very significantly. So polls do measure something.

Now to the question of why the vast majority in Russia believe that the country is on the right track, I think, is because there is a very strong sense of clinging toward normalcy.

Something extraordinary has been happening in Russia for way over a year, the bloody war in which many Russians have gotten killed. But for many, there is an opportunity to turn their backs to the war, to try not to think about it, for their own emotional comfort. The authorities actually make such a perception possible.

This is especially true of the largest urban centers, and especially Moscow and St. Petersburg, where relatively few people have been drafted or otherwise forced to take part in the war. People are more likely to organize in cities that have a history of political rallies, so the government tries to make sure these people are least disturbed by the war.

Also, one should not underestimate the various social groups who benefit by the war financially. Of course, the obvious one is the military-industrial complex. It’s a lot of people and many more now as the government recruits more and more to work on military-industrial plans. It is the actual servicemen, and they have families, and the government has been delivering quite generously to the families, to those who fight and to their families if they get wounded or killed.

Also, the government has launched a generous program of social welfare for poor families with children, which also accounts for a large number of people. This gives a sense to many people in Russia that the government takes care of them. And this also reinforces a sense of “we should support the government.”

There’s always conspiracy theories about the US and their role. Have those been surfacing, in particular on Telegram, in the media, in light of the weekend’s mutiny?

Yes, state propaganda may look stilted as propaganda goes, but one thing that certainly is received really well is anti-Westernism and the vilification and resentment of the West, which has always been there ever since, I would say, the mid-’90s, late ’90s.

This propaganda that has intensified quite significantly, even in the months leading to the war, has fallen on fertile soil. And it has never been as persuasive as recently.

Putin has said for years that the West is there to do harm to Russia: “They want us weak.” Russia has been under sanctions — with new and countless rounds of sanctions — and now the West, including the United States, is openly saying, “We want to emasculate the Russian militarily,” so it would never be able to wage another war. This is said openly now. There used to be rhetoric in the West that in fact Putin is imagining it.

Now, on the actual mutiny and what’s been said about that. Putin personally didn’t directly blame the West for being behind Prigozhin. But he suggested that it suits the West fine, as he put it, “the neo-Nazi in Kyiv and their Western patrons.” He just stopped short of saying actually the West dispatched Prigozhin to stage this mutiny.

What will you be watching in the coming days and weeks in the Russian media?

One thing is already clear now: These, I would say, are desperate attempts by the government — by the loyalists, by state media, national television — to portray the events of the 23rd and 24th as victorious for the Kremlin.

Putin started it himself in his statement. He sounded like he triumphed. He thanked the Russian people for what he referred to as their unity, their patriotism, their fortitude. He congratulated them even on their solidarity, and the solidarity of the government and the people.

This is an indication the mutiny has been a blow on the Kremlin. I don’t mean militarily, but certainly in terms of Putin’s elites, not to mention people outside of Russia, saw that he was helpless. And he had to take back his own pledge to punish them, which he made in his address on the 24th in the morning, and then he left and his whereabouts were unknown, which also suggests that he didn’t act bravely, to put it mildly.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that maybe at least some part of the Russian society see him this way, and are disappointed in him. And those who hadn’t supported him maybe now have a new strong argument to think of him as an officiant, as not a master of his own country, in a sense, and maybe as a coward. So what I would be looking at is whether this is reflected in the public opinion polls and especially focus groups. I would be looking at public perception, whether it is likely to change or whether people would actually put it behind them.

What is arguably more important at this moment is the mood among the elites. Because, unlike the public at large, the elites cannot put it behind them and forget about it. This is their lives.

There has been secondary evidence — of course, no official in Russia can afford to be critical of Putin in public — but there’s been many articles, many analyses by people who claim to have some knowledge about what goes on inside, that there is rising discontent among the elites, except that they don’t dare show it.